|

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

by Sharon Kennedy The stories of Bouki and Malice are some of the most famous trickster tales in Haiti. Malice (pronounced "mal-EECE") is the trickster and Bouki ("BOO-key") is usually very easy to trick. It is possible to hear these stories told not only in Haiti but right here in Medford, by Haitian-American resident Nathalie Fanfan. The video here is the first Bouki and Malice story told me by Nathalie on November 15, 2012. Malice tricks Bouki into bathing his mother with scalding hot water. The result of this, as you can imagine, is not good! To help you understand this story you need to realize that Haitians say the word “bathing” as if it is “bath” with an “ing” on it. They don’t change the sound of the vowel the way that Americans are used to. Nathalie told another Bouki story off camera about Malice explaining to Bouki that if you are hungry, you can simply eat your mother. Apparently Bouki is quite hungry, and doesn’t have anything else to eat, so when he looks around and sees that Malice’s mother is missing from Malice’s house, he assumes that he is being told the truth. Actually Malice has hidden his mother and his mother is in no danger of being eaten at all. However, Bouki goes home and eats his mother. Later he finds out that Malice’s mother is alive and well. So why would people tell stories about eating or killing their mothers? I don’t have the answer for this but I will just say that Haiti is not the only country, which has tales like this. Many of the people in Haiti, Ireland, Mexico, and Cambodia who are telling this kind of tale are very poor and very hungry. They are poor and hungry in ways that most people in the United States can’t really imagine. And one more thing: where ever storytelling is alive and well and people are still regularly engaging in telling each other tales, nothing is sanitized, nothing is politically correct, children are not protected from hearing most of what is told and harsh realities are confronted within the framework of a tale with no sugar-coating. On the other hand I do hope any one reading this realizes that, during the storytelling, there is a great deal of head shaking and laughing about how incredibly guillable Bouki is. No one who is listening to the story will go back home afterwards and kill his mother. "Kric? Krac! Would you like to hear another story?" That is how you ask for one in Haiti. And Nathalie told me there is another way to begin a story telling — you say, “Tim Tim, Bois Cherche!” (In Creole, “Bois Cherche” means “Look and see if there is something in your mouth”!) So, Tim, Tim, Bois Cherche! Here is another story from Nathalie... Once there was a loup garou. A loup garou is someone who looks like a regular person during the day but can change into a werewolf (in English) at night. This loup garou ate two little children belonging to a wife and her husband. They went to the hungan (a voodoo priest) to find out who it was that did this terrible thing. The hungan said it was the grandmother — the mother’s mother. For this reason they put her to death. Many years later when the other grandmother died (the father’s mother) she felt that needed to confess something on her deathbed. Her confession was that she was the loup garou and she was the one who killed the children. So they had put the wrong grandmother to death. This reminds me very much of a story I heard when I was traveling in Ireland in 1987. I was in County Clare and a storyteller told me that many years before there was a small child who was becoming more and more sickly in County Kerry. Finally when the child died the mother was accused of being a witch and of having killed her child. “They dragged her out of the house and burned her in a bonfire. “Years later didn’t they realize the poor woman had done nothing of the kind? The child just had a sickness and died. After that it was like a black mark against the Kerry people. Oh, it went against the Kerry people all right. That they had burned that mother for a witch.” So, in both cases, we learn from the stories that what was thought at the time to be right and proper and a good response, proves to be quite the opposite in the end. In the Irish story we (or the people in Ireland at that time, and for many years afterwards, as they listen to the story) are being warned about the power (and possible wrong headedness) of a mob. In Haiti the listeners are being told to think twice about what their greatly revered hungan (priest) says. Maybe they are wondering if his authority should be questioned? He clearly came to the wrong conclusion and an innocent woman was put to death. At least a few of you are now wondering, as you read, this whether you are supposed to accept that loup garou are real. I can’t answer that question either. All I can say is that French Canadians have loup garou in their stories too. Why would anyone want to tell a story about eating their own mother? Why would anyone want to tell a story about eating their own mother? Instead of answering that question I will tell you about a story from Ireland. In the tale of “Huddon, Duddon, and Donal O’Leary.” Huddon and Duddon tell Donal that the reason they suddenly have plenty of money is because they killed their mothers and took the ashes into town and sold them. The setup here is exactly the same as it is in the Haitian story. Donal is like Bouki. He is a bit of a simpleton, and based on what he has heard, he kills his mother and goes to town to sell her ashes. He is totally honest about what he is selling and so he is arrested and put in jail (in one version) and just run out of town (in another). Meanwhile there is a version of this story called “Ashes for Sale” from Mexico in which a similiar trick is played, except no-one is killed. “Naldo” convinces “Pedro” to take all of his ashes from the fireplace and go to town to sell them. Of course Pedro does not do very well and then the story continues on in a completely different direction. It is very likely that in an earlier version of this Mexican story, the ashes came from a more sinister place, as they do in the Haitian and Irish story above. And finally, one time in the back of a darkened library in Lowell, Mass., where a film was being shown to a group of children, (so that we had to speak in whispers), a Cambodian man told me a story which he heard when he was little. He translated it from the Khmer and, as he did, I listened in absolute amazement as he told the Cambodian version of “Huddon, Duddon, and Donal O’Leary.” It was almost exactly the same, and yes, it included selling the ashes of a dead mother. Why does such a set -up for a story tickle the funny bone of the people who are listening to this kind of tale in Haiti, Ireland, Cambodia, or Mexico? I’m sure the answers are very complex so I will just offer one of the many possibilities which has occurred to me. Maybe one day a few people were sitting around talking about how little they have and how poor they are and wondering how they would ever get ahead and do well and make money. Then someone in the group laughed and said “well, too bad you can’t make money from selling ashes — or your own dead mother.” Then someone else said, “I bet Donal O’Leary (or “Bouki”) would actually believe a scheme like that could work! Donal would try selling his dead mother if you told him to!” And, just for the record, when I have performed the Irish “Huddon, Duddon, and Donal O’Leary” story for an adult audience, a few people may have recoiled from the theme but most laughed and laughed, probably almost as much as the people who listened to the story in the first place, in some very poor village in Ireland long ago. |

|---|

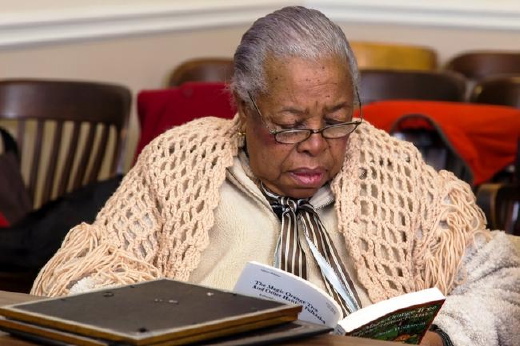

Nathalie Fanfan—The Stories of Bouki and Malice

Nathalie Fanfan—The Stories of Bouki and Malice